To conclude, and that I may not trespass too far on your Patience and good Nature, or take up too much of your Time from the more important Affairs of your Families, I hereby ingenuously acknowledge, that I have exerted all the Art and Industry I can boast of, in compleating this Pocket-Book, complied for your Service, and intended as your daily Remembrancer; and that I an not conscious to myself of having omitted one Article of any real Importance to be further known…

This morning, I had a plan. A really good plan for today’s post and the idea to also prep one for next week (and see if I can get back on a weekly posting schedule after a busy last few months). While scanning materials for the second post, I discovered some new culinary history tidbits that were too good not to share today. So next week, I’ll tell you about our new agricultural ephemera collection. This week, we’re going back to the mid-18th century, to Sarah Harrison’s The house-keeper’s pocket-book, and compleat family cook : containing above twelve hundred curious and uncommon receipts in cookery, pastry, preserving, pickling, candying, collaring, &c., with plain and easy instructions for preparing and dressing every thing suitable for an elegant entertainment, from two dishes to five or ten, &c., and directions for ranging them in their proper order. First published somewhere in the late 1730s (probably, our recently acquired copy is the later 7th edition from 1760. The quote at the above comes from Harrison’s own introduction to the book.

Yes, another one of those books with a lengthy title that takes a whole page. (I”ll stick with The House-Keeper’s Pocket-Book for the sake of my typing skills today.) Mrs. Harrison manages to pack of lot of information into 215 pages (plus another 36 for the added Every One Their Own Physician by Mary Morris).

Primarily, she provides recipes and suggested menus (bills of fare) for a year. Then, toward the end, we get a some of the more “housekeeping” or “household recipe” side of things: directions for removing stains, cleaning dishes, managing animals and livestock, and even a bit of distilling/brewing. Much in the British style, there is a significant section in the book on pies (not just the sweet, but the savory). And as chance would have it, I stumbled on to page 60 and the word “umbles.”

While working this this culinary history materials here has provided this archivist quite an education, I, too, get stumped on occasion. For those of you who already know the word, kudos! For those of you bit less acquainted with the term, “umbles” refers to the organ meats of deer (and comes from the French “noumbles”). In this case, we have a recipe for “Umble Pie.” This recipe for “umble pie,” with its humble ingredients of deer innards, very likely led to the phrase “humble pie.” From dinner recipe to idiomatic expression in a single bound!

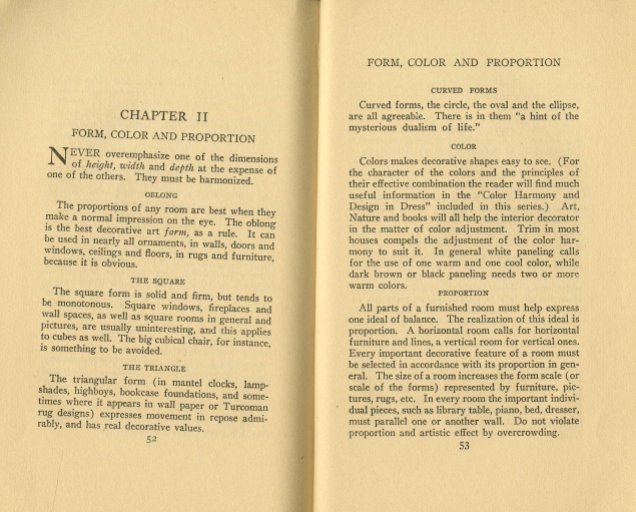

The House-Keeper’s Pocket-Book also includes a few illustrations, like these plans for placing parts of a dinner course:

(The small “L2” at the bottom of the page was used to help construct the book, whose pages would have been printed in large sheets, then folded, cut, and sewn together.)

(The small “L2” at the bottom of the page was used to help construct the book, whose pages would have been printed in large sheets, then folded, cut, and sewn together.)

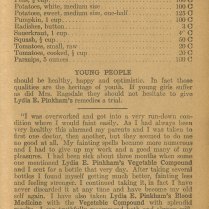

It wouldn’t be culinary history if we didn’t talk about one of our favorite topics: pickling. In 1760 (and when the earlier editions of the book were written), this was a main method of preservation. So, you could (and would!) pickle just about everything. Below is one of the page spreads on the subject and includes some items we recognize today, as well as a couple of ingredients (or at least terms) that are a bit less so.  “Codlins” (also codlings) refers to a family of apples with a particular shape, usually use for cooking. “Samphire” is a plant that grows on rocks near the sea. Its leaves were often used pickling.

“Codlins” (also codlings) refers to a family of apples with a particular shape, usually use for cooking. “Samphire” is a plant that grows on rocks near the sea. Its leaves were often used pickling.

Sarah Harrison’s book would go on to have several other editions after this 7th one, but eventually, it was a cookbook that became more rare or unique to collectors and collections. We were lucky and happy to acquire this copy several months ago and we hope some one of you take the opportunity to come use it, too! Sadly, it hasn’t been scanned in its entirety for public viewing, but that may be a future task for us to undertake. In the meantime, you can always send us your (h)umble queries on Mrs. Harrison’s work.