Ellen Henrietta Swallow (later Richards) was born in 1842. In 1870, she graduated from Vassar College with a Bachelors of Science–she focused her studies largely in astronomy. In 1871, far from completed with her own education, she applied to, and was accepted, to MIT. She was the first woman to attend the school, graduating from there with a second Bachelors of Science, this time in Chemistry. The same year, she received a Master of Arts from Vassar. In 1875, she married Robert Richards, a professor. From 1873 to 1884, she taught MIT and worked as an assistant to professors and researchers, without a title for many of those first years. She was the driving force behind development of the “Women’s Laboratory,” which, in turn, expanded the education opportunities in the sciences for women at MIT until it closed and the school began offering regular undergraduate opportunities for women. During this time, she also began working for the Board of Health in Massachusetts (which would lead to some of her later efforts). Much of her work efforts overlapped: she taught at MIT while working for the Board of Health, and for about a decade in there, also worked for Manufacturers Mutual Fire Insurance Co., and would later consult for companies, too. The history of her employment at MIT is complex, but between 1873 and 1911, she taught in chemistry, biology, and mineralogy, at the very least. We know that in 1879, she was an assistant professor in chemical analysis, industrial chemistry, mineralogy, and applied biology, but may not have been receiving a salary. By 1884, she was known as an instructor in sanitary chemistry. Shortly before she died, in 1910, Smith College presented her with an honorary degree Doctor of Science in light of her life-long efforts. She passed away in 1911, leaving a legacy of education, public health, and as a pioneer for women in science.

Some of her work in chemistry focused on issues of public health and other parts on issues of food and its chemistry. While she isn’t the traditional culinary history writer we often talk about on the blog, her contributions to aspects of the field, and related ones, were ground-breaking. In fact, there wasn’t much of the traditional about Ellen Richards, which is probably a wonderful thing for both her students and those that followed her. Her work and some of her 15 books would feed into the development household management and domestic science/education in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Which is probably an indication that we should look at some examples!

The work of hers that we’ve actually talked about before is The Dietary Computer, Explanatory Pamphlet; the Pamphlet Containing Tables of Food Composition, Lists of Prices, Weights, and Measures, Selected Recipes for the Slips, Directions for using the Same. I won’t rewrite the post, but if you haven’t followed us since 2012, or if you’ve forgotten, it’s well worth a look.

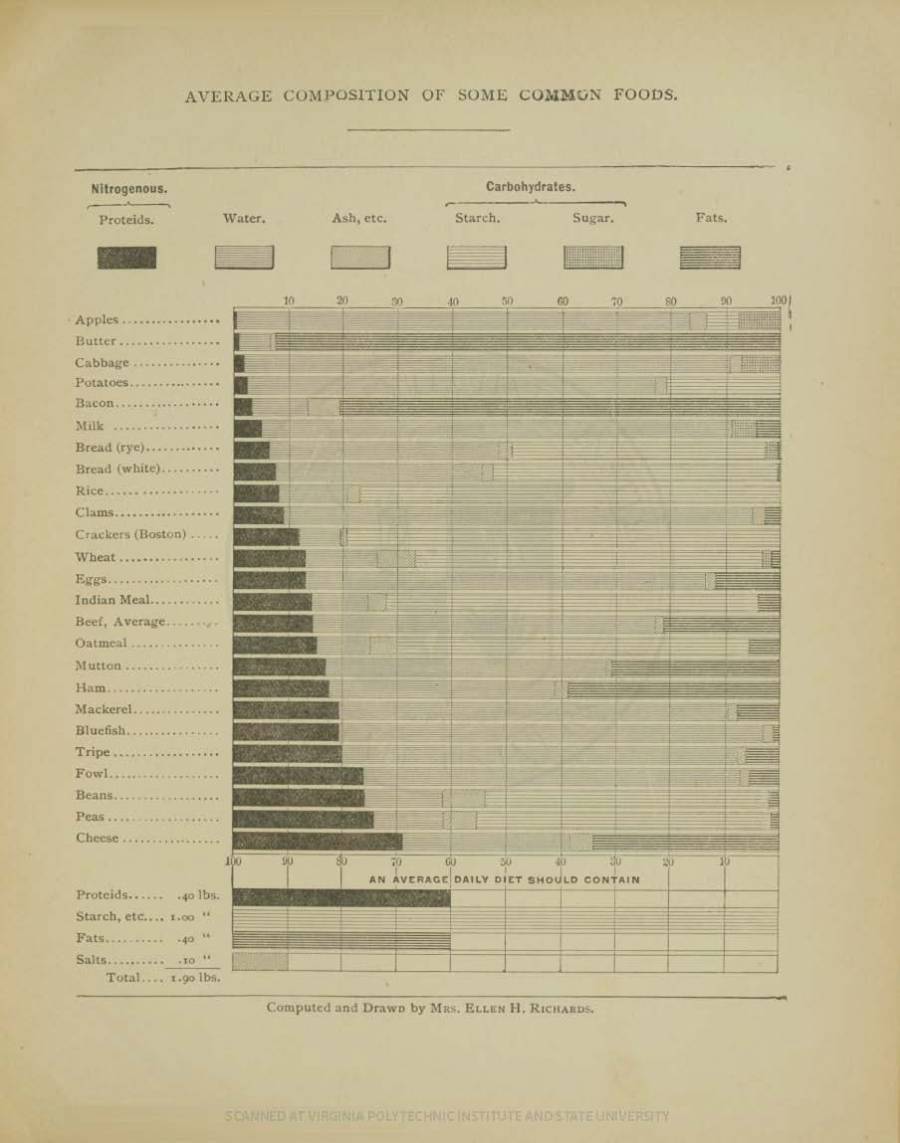

Her work often appeared within the books of others, since her research led to essays, charts, and even the hand calculated and hand drawn tables included in The Science of Nutrition from 1896:

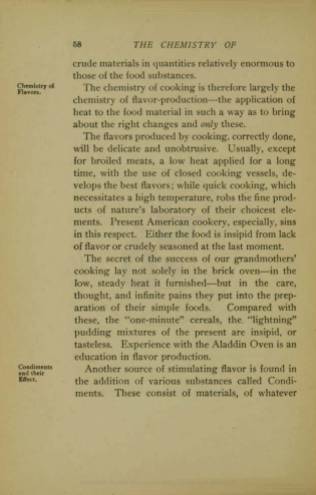

One of the stand-outs for me is the way in which Richards brought chemistry into the home, using her books as a way to education women who may not have the opportunities to study in a formal setting. She reinforced the importance of knowledge for women and the benefits of understand what she refers to–quite perfectly, I think–as the “Chemistry of Common Life.” The Chemistry of Cooking and Cleaning: A Manual for Housekeepers covers aspects of food science, the chemistry behind cooking techniques and ingredients, the chemistry and public heath values of cleanliness, and even contains research into the addition or adulteration of cleaning products (see page 113 below)!

Richards was an extremely prolific author and co-author for many years. Here in Special Collections five of her books (titles in bold below) and there are another two available through the University Libraries. Many of her works went through multiple editions, too! In addition to the titles we have, she wrote on other aspects of chemistry, food cost studies, public health, education in schools, and contributed to other pamphlets from corporations.

- The Rumford Kitchen: The Exhibit of The New England Kitchen at the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893 (included content by Richards)

- Atkinson, Edward. The Science of Nutrition. Treatise upon the Science of Nutrition…The Aladdin Oven, invented by Edward Atkinson. What It Is. What It Does. How It Does It. Dietaries Carefully Computed, under the Direction of Mrs. Ellen H. Richards. Tests of the Slow Methods of Cooking in the Aladdin Oven, by Mrs. Mary H. Abel and Miss Maria Daniell, with Instructions and Recipes. Nutritive Values of Food Materials,

Collated from the Writings of Prof. W. O. Atwater. Appendix: Letters and Reports, 1896 (available online) - The Dietary Computer, Explanatory Pamphlet; the Pamphlet Containing Tables of Food Composition, Lists of Prices, Weights, and Measures, Selected Recipes for the Slips, Directions for using the Same, 1902 (With Louise Harding Williams)

- First Lessons in Food and Diet, c.1904

- The Chemistry of Cooking and Cleaning: A Manual for Housekeepers, 1907 (available online)

- The Cost of Cleanness, 1908

- The Art of Living Right, 1915

On a citation note, I’m indebted to two really great (and compact) biographies of Richards for the information I’m sharing this week, one from the MIT Libraries and the other from the American Chemical Society. The MIT site also includes the link to the digitized version of Richards’ thesis for her Chemistry degree! I recommend both, since what I’ve presented here is an even shorter version.

![Richards, Ellen H., and Louise Harding Williams. The Dietary Computer. Explanatory Pamphlet; The Pamphlet Containing Tables of Food Composition, Lists of Prices, Weights, and Measures, Selected Recipes for the Slips, Directions for Using the Same. New York: J. Wiley & sons; [etc., etc.], 1902. Title Page](https://whatscookinvt.files.wordpress.com/2012/11/dietary001.jpg?w=316&resize=316%2C316&h=316#038;h=316&crop=1)