As promised, this week we’re at the end of processing the Educational Cookery Collection (yay)! And, I remembered to take pictures while I was working on the collection this week, so there are plenty of visuals below!

After all that alphabetical sorting last week, I ended up with a stack of 16 folders that look, well, like this:

Each folder has the collection number and title on the left side, the folder title in the center, and the box-folder number on the right side. Given the final decision to sort the collection by creator name, there are 15 folders for letters of the alphabet and one for materials without clear creators. They sat in a stack on my desk as I worked through creating bibliographies for each folder, at which point I was shifting in their new home–an acid-free box:

In the end, they don’t take up the whole box, but that’s okay. I used the lid as a temporary spacer to keep folders from slumping or falling over, which can damage the contents over time (that’s also why, in the picture above, I turned the box on its side as I started added the first few folders to it). Before I put the box on the shelf, I made a more permanent spacer from some left over cardboard. (We keep many different kinds of scraps around here that come in handy for reuse: cardboard, old boxes, mylar, matboard…Plenty of archivists like to reuse and creatively “upcycle” where they can!) Also, this means we have space to add more items later!

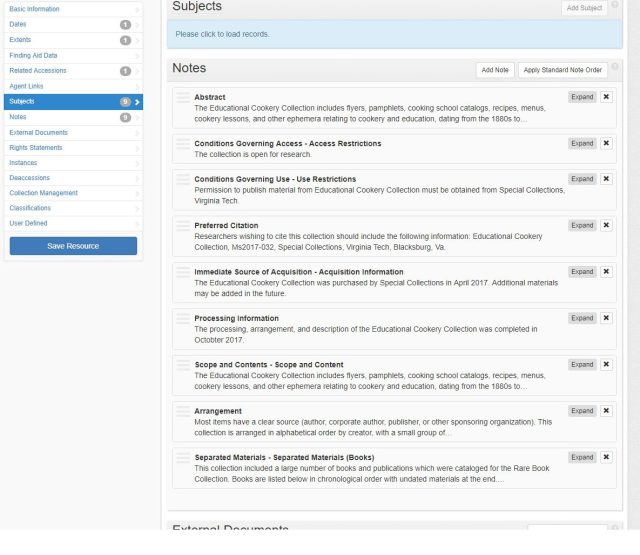

The other part of processing, of course, is the intellectual description and processing. We use software called ArchivesSpace, which lets us keep track of new accessions, digital objects (scans), subjects, and creators, and helps us create the finding aids we put in Virginia Heritage. If you’re curious what it looks like, this is a screenshot with the list of folders for this collection. The navigation links in the lower left help us jump around the rest of the record below, since more complex collections can have a lot of content.

As I finished writing up the notes in the collection, I also grabbed a screenshot of those. The software consolidates sections with a lot of content (like the Subjects, in this case) and when you are viewing a section (like the Notes), shows you shortened versions, which you can expand and edit. I promise, it can save a fair bit of scrolling if you’re trying to get a specific section. The sidebar on the left shows you, at a glance, connections between this and other records or how many elements there are in a given section. In this collection, for example, there’s a link between this and one existing accession record, a single “date” component, and 9 notes.

Looking at that screenshot reminded me I missed something. That left side navigation can also help with that. If you’re expecting a number next to a part of the record and it’s not there, it’s a good reminder you might need to fix that! Anyway, this resource record, as it’s called, is what we can export from ArchivesSpace, tweak a little bit, and put into Virginia Heritage for researchers everywhere to discover. I finished up the finding aid on Thursday morning, along with my final checklist of items for collections. (Seriously, I have a spreadsheet checklist for collections I process–it helps me keep track of what gets processed, as well as all the little administrative and practical steps that going along with making it discoverable!)

As I mentioned last week, every collection is a little different and I wouldn’t be surprised if we talk about processing again in the future. I hope it gives some insight into what goes on behind-the-scenes so researchers can find our materials to use. And a little bit about what those of us who work behind-the-scenes do! The finding aid for the Educational Cookery Collection (Ms2017-032) is now available online and the collection is in its home on the shelf:

So, we encourage you to come by and take a look when you have a chance! I expect this collection will grow in the future (much like some of our ephemera-based collections), and I’m looking forward to finding out what we add next!