So, as is the way of things, your usual archivist/blogger Kira has found herself a new project. (I want to talk about it, but it means a more text-based blog post this week–apologies for that in advance.) Good news: It’s for the benefit of everyone and it will provide a new access point to some of our materials–I think! Additional good news: It only took a set amount of time to accomplish and didn’t interfere with all the other projects. Bad news: Well, there isn’t any!

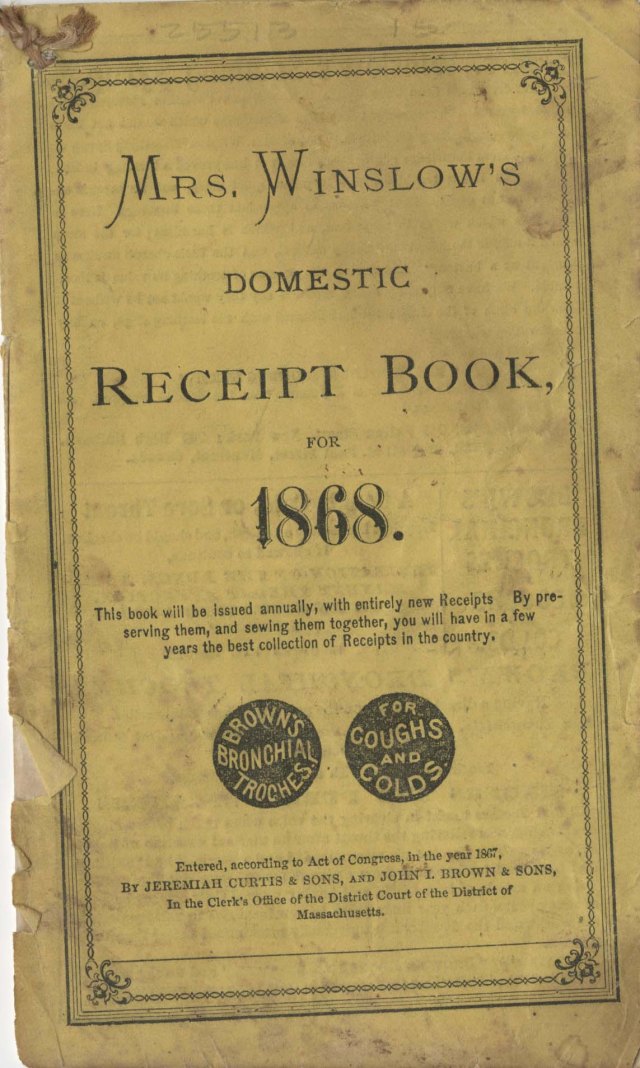

To explain: For folks interested in the history of medicine, there’s a really great resource out there from the National Library of Medicine: the History of Medicine Finding Aids Consortium. This resource brings together finding aids from institutions around the country that deal with aspects of medicine and allied sciences. Some of our food and drink, local/regional history, and Civil War materials touch on some related aspects of medicine, including patent medicine, folk/traditional medicine, practitioners, disease history/research, and even military medicine history. Which, it turns out, does make us good candidates to contribute content to this resource!

To further explain: In a case of perfect timing, we may also have some faculty and classes interested in history of medicine materials. So, I’ve spent a few hours this week identifying collections that relate to aspects of medicine and started working on a way to bring those collections together virtually. Namely, through the use of a new subject heading for this purpose: “Folk, historical, and patent medicine.” This heading itself is being used as an umbrella term to gather collections (I realize it’s a pretty wide scope). So, in addition, we are including more specific, and authoritative, headings in these collections, too. These are formal headings created by the Library of Congress for cataloging books (and, in our case, we’re using them to describe manuscript collections). For this project, we’re using “Medicine” (for collections relating to the history of medicine, medical practices, doctors, and patients, and the like), “Patent medicine” (for collections relating to the history of propriety, patented, over the counter “cure,” often plant and/or alcohol based), and “Traditional medicine” (for collections relating to home remedies and folk medicine). Because we also have some Civil War collections dealing the the military perspective, you may also see “Medicine, Military–History” appearing in collections.

Getting these collections into the NLM consortia will take a little time, but the good news is that you can already access these collection using these headings through Virginia Heritage, the statewide finding aid portal! There are 41 collections already tagged with these subjects and I’m working identifying some more. Then I’ll also be setting up a “Sources for Selected Topics” page on our food and drink LibGuide about home remedies, folk medicine, and patent medicines! We encourage you to take a look–and check back. You never know what might interest you!

![TX715.H834_1881_4 These "Walnut Pickles" include a quite precise direction that they should be "gather[ed]...about the 10th of June, when you can stick a pin through them"](https://whatscookinvt.files.wordpress.com/2017/05/tx715-h834_1881_4.jpg?w=156&resize=156%2C238&h=238#038;h=238)