For the start of Women’s History Month (or, as we call it on the Virginia Tech campus, Women’s Month), I thought we would, oddly enough, talk about the woman who didn’t exist: Betty Crocker. The idea of Betty Crocker was (and remains) influential. And yet, she doesn’t (and didn’t) exist as a person–Crocker is an identity and a brand. On the one hand, we could argue that perhaps a fictional identity isn’t the way to sell products or best way to represent women. On the other hand, the fact is, it worked. Really, really well. Which is why it seems fair to take a look at just what this character did for culinary history.

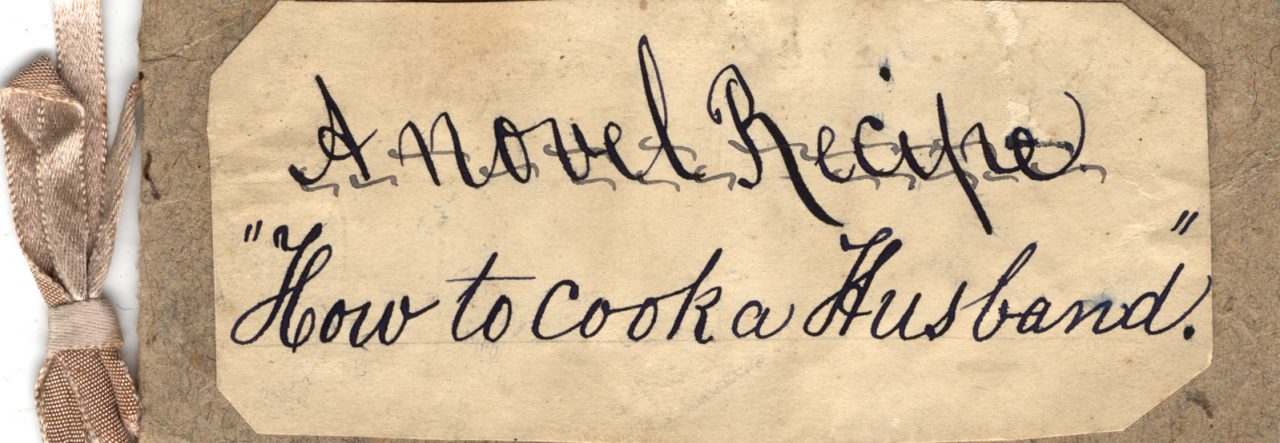

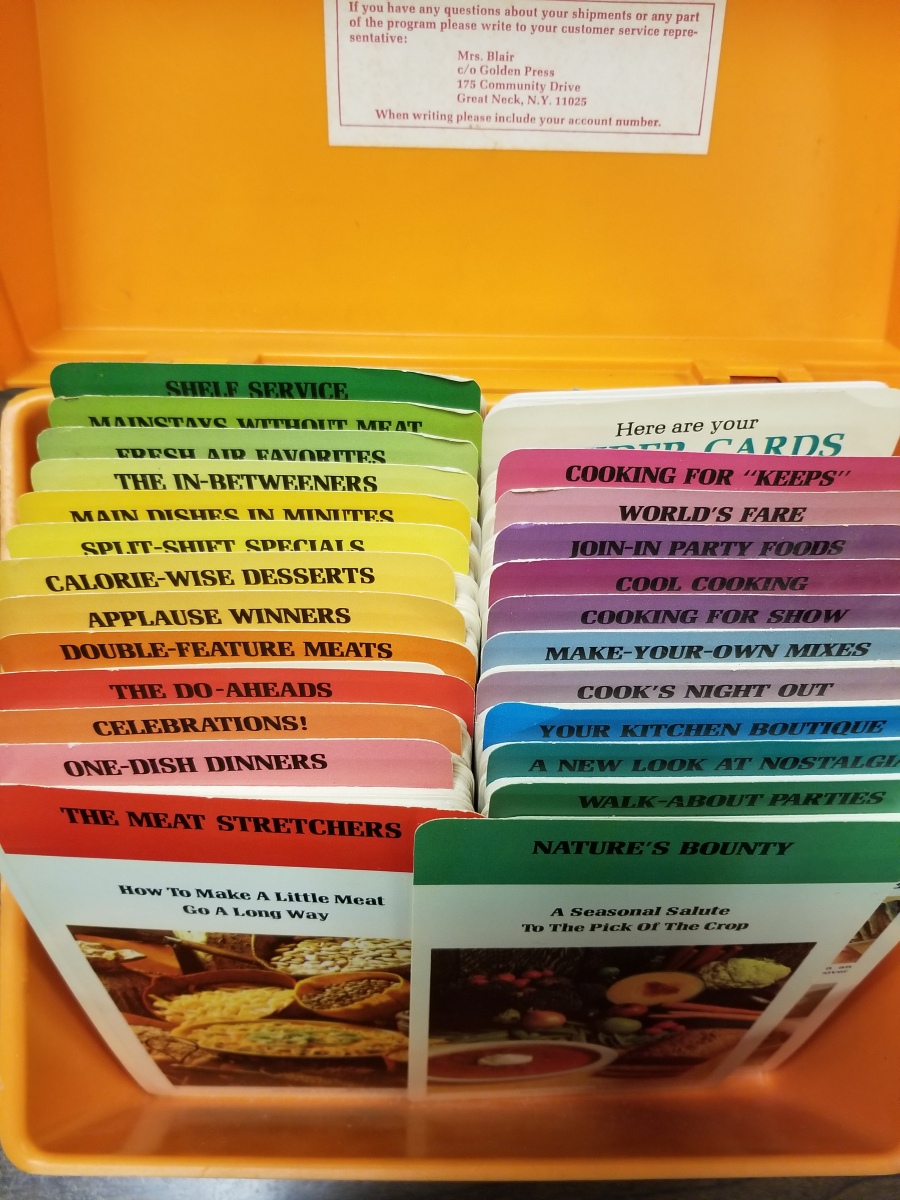

We’ve highlighted a couple of specific publications “by” Crocker in the past: Betty Crocker & Salads and Betty Crocker & Outdoor Entertaining. This week, we’ll add some more to the mix. Special Collections houses 21 books and publications attributed to Betty Crocker, including my beloved Betty Crocker card libraries. If you add in books housed in the circulating collection, that total doubles. You can view a list of the publications online. And that barely scratches the surface of materials attributed to this identity and image. There are books, card libraries, pamphlets (we have those in some manuscript collections, too), flyers/single-page instruction sheets, individual recipes cards, advertisements, and more.

So, who was Betty Crocker, then? The idea behind her creation in 1921 was to have a female persona/representation for Washburn Crosby (by the end of the decade, the company would merge with others to form General Mills). The company’s advertising department was all male, but their intended audience was, of course, women. They needed an image to sell that. However, this is not to say that there weren’t women involved in helping to build the persona. When “Betty Crocker” got a radio show in 1924, she was voiced by a home economist on staff, Blanche Ingersoll. The publications that began to flow out to the public written by Betty were really the work of Marjorie Child Husted and a team of home economists who created, tested, and marketed the recipes. Husted worked on getting the persona of Betty Crocker to engage with real people for items like “Let the Stars Show You How to Take a Trick a Day with Bisquick” from 1935. The first portrait of Betty Crocker appeared on materials in 1936, giving further credence to the identity.

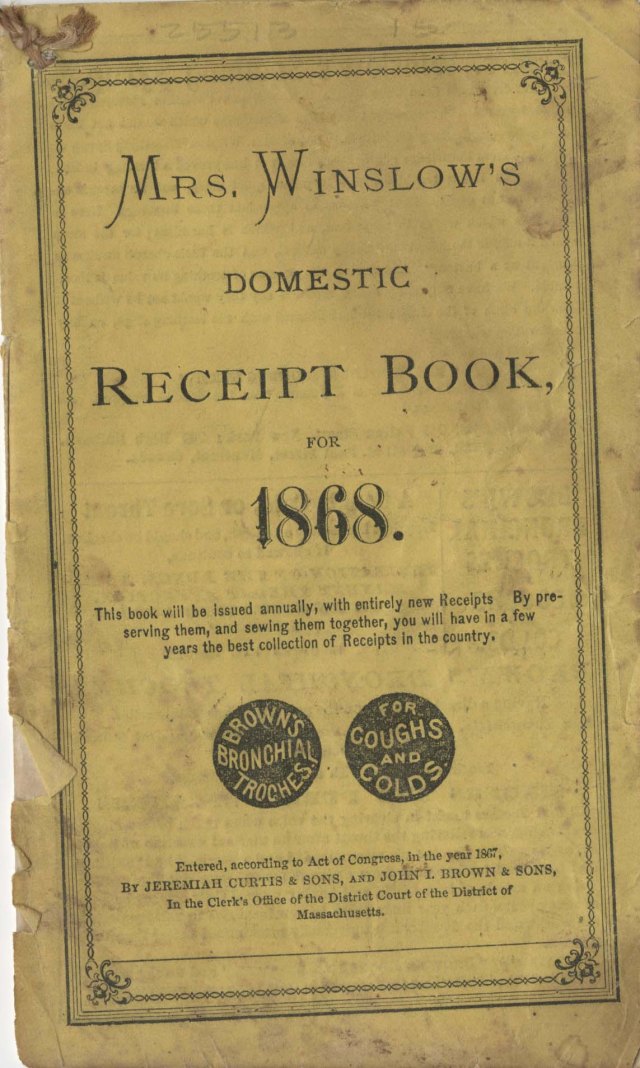

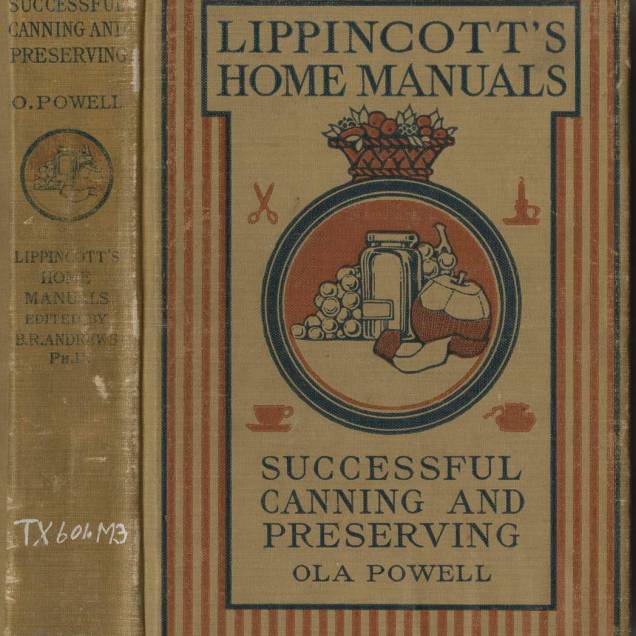

During decades of change, Betty Crocker’s work was adapted to meet needs of women around the nation: Publications focused on how to stretch foods during the Great Depression and how to cook under rationing conditions in World War II. While all of these things could have also been provided by a single author, radio host, home economist, etc. (or a series of them over time), as we’ve seen with other companies, we might also consider there is something to be said for the consistent image that we’ve seen now for more than 90 years. The idea of Betty Crocker as a constant companion in the kitchen, one who rises to the challenges of changing times and even reflects back some of what is going on for women during that turmoil. (*see note at the end of the post)

If you’d like to know more about the history and evolution of Betty Crocker, there are some resources at your fingertips (and beyond). I discovered the MNopedia article on Crocker, which helped me write this post. There’s a chapter in The Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media has a brief article that contains images of Crocker of time. And Laura Shapiro’s book, Something from the Oven: Reinventing Dinner in 1950’s America, includes at least part of a chapter on Betty Crocker.

*On a side note, I didn’t know much about Marjorie Child Husted before I started this post, though I had seen the name. It was interesting to learn that in addition to her work with this persona, “during the war, Husted worried that women were not being honored for their work in the home. She developed the Betty Crocker American Home Legion in 1944 to recognize women for their contributions. Husted championed the rights of women in the workplace, criticizing General Mills and other companies for discriminating against their female employees.” (http://www.mnopedia.org/person/betty-crocker) It seems that much of what she did was tied to Betty Crocker, which gives us another perspective on both Husted and what she intended Crocker to be.

![Natural color meat identification kit [flash card] : complete with suggestions for using and instructor's key, c.1960s? List of cuts, Part I](https://whatscookinvt.files.wordpress.com/2012/01/meatid004.jpg?w=600&h=437)

![Natural color meat identification kit [flash card] : complete with suggestions for using and instructor's key, c.1960s? List of cuts, Part II](https://whatscookinvt.files.wordpress.com/2012/01/meatid005.jpg?w=600&h=437)

![Natural color meat identification kit [flash card] : complete with suggestions for using and instructor's key, c.1960s? Box lid. Natural color meat identification kit.](https://whatscookinvt.files.wordpress.com/2012/01/meatid001.jpg?w=316&resize=316%2C316&h=316#038;h=316&crop=1)

![Natural color meat identification kit [flash card] : complete with suggestions for using and instructor's key, c.1960s? Suggestions for use, Part 1](https://whatscookinvt.files.wordpress.com/2012/01/meatid002.jpg?w=316&resize=316%2C316&h=316#038;h=316&crop=1)

![Natural color meat identification kit [flash card] : complete with suggestions for using and instructor's key, c.1960s? Suggestions for use, Part 2](https://whatscookinvt.files.wordpress.com/2012/01/meatid003.jpg?w=316&resize=316%2C316&h=316#038;h=316&crop=1)

![Natural color meat identification kit [flash card] : complete with suggestions for using and instructor's key, c.1960s? #8](https://whatscookinvt.files.wordpress.com/2012/01/meatid008.jpg?w=316&resize=316%2C316&h=316#038;h=316&crop=1)

![Natural color meat identification kit [flash card] : complete with suggestions for using and instructor's key, c.1960s? #15](https://whatscookinvt.files.wordpress.com/2012/01/meatid015.jpg?w=316&resize=316%2C316&h=316#038;h=316&crop=1)

![Natural color meat identification kit [flash card] : complete with suggestions for using and instructor's key, c.1960s? #43](https://whatscookinvt.files.wordpress.com/2012/01/meatid043.jpg?w=316&resize=316%2C316&h=316#038;h=316&crop=1)

![Natural color meat identification kit [flash card] : complete with suggestions for using and instructor's key, c.1960s? #63](https://whatscookinvt.files.wordpress.com/2012/01/meatid063.jpg?w=316&resize=316%2C316&h=316#038;h=316&crop=1)

![Natural color meat identification kit [flash card] : complete with suggestions for using and instructor's key, c.1960s? #81](https://whatscookinvt.files.wordpress.com/2012/01/meatid081.jpg?w=316&resize=316%2C316&h=316#038;h=316&crop=1)

![Natural color meat identification kit [flash card] : complete with suggestions for using and instructor's key, c.1960s? #102](https://whatscookinvt.files.wordpress.com/2012/01/meatid102.jpg?w=316&resize=316%2C316&h=316#038;h=316&crop=1)

![Natural color meat identification kit [flash card] : complete with suggestions for using and instructor's key, c.1960s? #105](https://whatscookinvt.files.wordpress.com/2012/01/meatid105.jpg?w=316&resize=316%2C316&h=316#038;h=316&crop=1)