Like a good blogger, I have a constant list of ideas in a file somewhere: culinary books, ephemera, or collections to write about some day. Today’s feature has been on my list, probably since the day we got it (or very nearly). I forgot about it for a while, then put it on the list some months ago. It seems as good a day as any to look at an item about mail order booze…

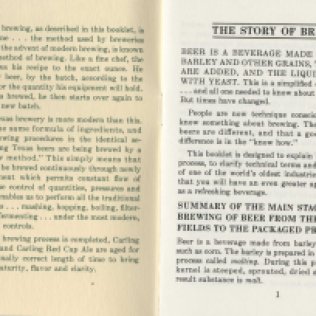

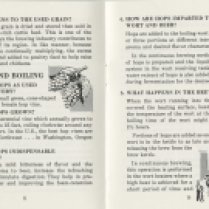

The image above is a c.1910s mail order price list from Lowenbach Bros. At the time we acquired the item, tempted as I was to lose hours on a single sheet of paper, I resisted. Which is to say, I didn’t go down the genealogy road and attempt to identify or locate one or more actual Lowenbach brothers who may have been connected to the business. So, you can imagine how excited I was to do a little digging this morning for the first time in 4+ years and discover someone else was very interested in this family and had written about it on a blog devoted to the pre-Prohibition whiskey industry. So, if you want to learn about the Lowenbach family, which included three generations, check out the post on “Those Pre-Pro Whiskey Men.” It’s worth noting that the referenced blog post points the origins of the business being even closer to Blacksburg than Alexandria–it was in Harrisonburg!

(Hmm, what? Where were we? I may have been a bit distracted by the discovery of that blog…)

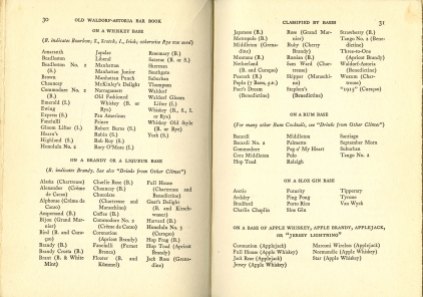

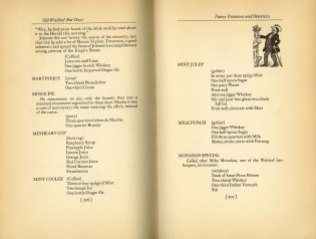

Anyway, our collection consists of this single mail order flyer. If you’re a cocktail historian or fan, many or all of the brands listed may seem unfamiliar. While there are certain brands and distillery locations that have been around for the long haul (a version of Old Crow, for example, has been around since the 1830s, though it’s had many evolutions). There were also plenty of more short-lived ones, too. And, as we know, Prohibition took a lot of business out of the running–including the Lowenbach Bros. I suspect this price list dates to the early 1910s, as the company was shut down by the ban and didn’t reopen afterward (at least not under the same or a similar name). I also love that the flyer includes bottled cocktails in three kinds from three different companies. Bottled cocktails have been around since the early days and while some version of them has always been on the shelves, there was a distinct decline in the latter half of the 20th century. Interest in them is on the rise again, as well as in barrel-aged cocktails. I feel like the Lowenbachs would have been behind that trend, too. After all barrels have always been integral to distilling and transporting alcohol.

I digitized the item for the post and since the whole collection is this one item, I was able to add to our digital collection site. You can look at it in on the web here: https://digitalsc.lib.vt.edu/items/show/6946. You can also read the finding aid online for the collection, too (though it may be time to re-visit it and add a bit more).

Items like this may seem odd or out of place, but they can still give us some great insight into cocktail culture and alcohol history. We’re here all summer, if you need some cocktail (or culinary) inspiration or just want to dig through some fun ephemera. You never know what you might find!