Since there are FIVE Thursdays in March this year, you’re getting a bonus gift: Another women’s history month profile!

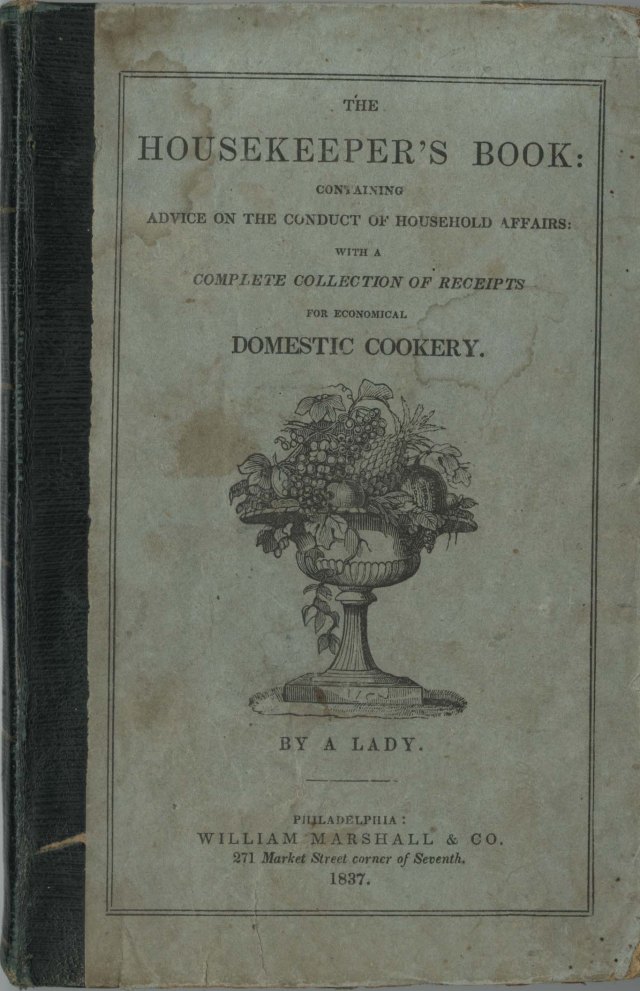

We only have one book at the University Libraries by Susannah Carter, The Frugal Housewife: or, Complete Woman Cook: Wherein the Art of Dressing All Sorts of Viands, with Cleanliness, Decency, and Elegance, is Explained in Five Hundred Approved Receipts…to Which are Added, Various Bills of Fare, and a Proper Arrangement of Dinners, Two Courses, for Every Month of the Year. Of course, there’s a good reason we only have one book–it’s the only one she wrote…sort of. On the surface, it’s not as clear as a good broth. The thing about The Frugal Housewife is that is appeared on both sides of the pond with variant titles, most of which have either the same subtitle, or at least part of the same subtitle. Yes, it’s bit confusing, but there’s quite a story to come. But first, the book!!

Oh, and apologies for the use of pictures that includes weights this week. Our 1802 text block is wonderful condition. It was rebound, probably some time in the last 75 years. This will help to continue to preserve the text, but it’s also a very tight binding and using a flat surface (aka a scanner) would be detrimental to the book. I had to get creative.

The Frugal Housewife (1802), detail plates.

The Frugal Housewife (1802), title page.

The Frugal Housewife (1802), introduction and part of index.

The Frugal Housewife (1802), meat recipes.

The Frugal Housewife (1802), Lenten soups.

The Frugal Housewife (1802), tarts and cakes.

The Frugal Housewife (1802), on potting meat, fish, and fowl.

So, back to the story of this book’s many titles. For example, you might also see The Universal Housewife: or, Complete New Book of Cookery. Wherein the Art of Dressing All Sorts of Viands, with Cleanliness, Decency, and Elegance, is Explained in Five Hundred Approved New Receipts, … Together with the Best Methods of Potting, Collaring, Preserving, Drying, Candying, and Pickling. To which are Prefixed, Various Bills of Fare, for Dinners and Suppers in Every Month of the Year; and a Copious Index to the Whole (1770), which was the first version of the book. Or, there’s The Experienced Cook, and Housekeeper’s Guide. Giving the Art of Dressing All Sorts of Viands, with Cleanliness, Decency, and Elegance, is Explained in Five Hundred Approved New Receipts. With the Best Methods of Potting, Collaring, Preserving, Drying, Candying, Pickling, Making English Wines, and Distilling of Simples, with Twelve New Prints for the Arrangement of Dinners of Two Courses, for Every Month of the Year, etc. (1850).

Let’s take a step back for a moment. The first edition of The Universal Housewife probably appeared around 1765 in London and Dublin. The first appearance of the text in America was in Boston in 1772. This early colonial version included engraving by Paul Revere (how cool is that??). Variations on The Frugal Housewife title began as early as 1772. The only versions of The Experienced Cook and Housekeeper’s Guide variants appear to have been published in 1850. While we know nothing about the life of Susannah Carter, she was probably deceased by then. Assuming that she was at least 20 when the first edition came out in 1765, in 1850, she would have been 105 years old. These variants were not always the same book, as some elements were improved upon or edited for different versions. The year after our 1802, another edition was published in America that contains a whole new appendix of receipts specifically for the “American mode of cooking” (both processes and ingredients). Why all the changes? That’s a hard question to answer, but there were probably a lot of factors. Many hands go into writing, editing, printing, and publishing a volume like this, and many people might have been inclined to take liberties with a text. It may have been an attempt to appeal to different audiences, too.

There’s another reason we’re looking at Susannah Carter’s book this week, too. And it has a lot to do with some of the previous posts in this series. The Frugal Housewife: or, Complete Woman Cook was extremely influential in America. Remember Amelia Simmons and American Cookery, or the Art of Dressing Viands, Fish, Poultry, and Vegetables, and the Best Modes of Making Pastes, Puffs, Pies, Tarts, Puddings, Custards, and Preserves, and All Kinds of Cakes, from the Imperial Plum to Plain Cake: Adapted to this Country, and All Grades of Life (1796)? Part of that title might look familiar now. As it turns out, entire passages of American Cookery came from The Frugal Housewife: or, Complete Woman Cook. (Copyright and publishing was a different business in the late 18th century!) The 1803 appendix to the American edition of The Frugal Housewife: or, Complete Woman Cook that I mentioned? That same appendix appears in an 1805 edition of Hannah Glasse’s The Art of Cookery. And it is probably not original to Carter. It appears to have been translated from a Swedish text called Rural Oeconomy. And, to further complicate things, as you may recall, in 1829, Lydia Maria Child authored a cookbook called The Frugal Housewife. Child’s book was published in different editions America and the UK, which, as you might expect, let to even more confusion. In 1832, under pressure, she changed the title to The American Frugal Housewife (though the old title didn’t disappear abroad until after 1834). This book has quite a history to it, right?

You can view the 1803 American edition of The Frugal Housewife at the Michigan State University Libraries’ Feeding America project, complete with the Swedish translated appendix. You can also see an 1823 London edition through the Internet Archive.

We’ll be back with another post next week. In the meantime, though, remember to make your gravies and sauces a priority. They are, after all,the “chief excellence of all Cookery!”

![Richards, Ellen H., and Louise Harding Williams. The Dietary Computer. Explanatory Pamphlet; The Pamphlet Containing Tables of Food Composition, Lists of Prices, Weights, and Measures, Selected Recipes for the Slips, Directions for Using the Same. New York: J. Wiley & sons; [etc., etc.], 1902. Title Page](https://whatscookinvt.files.wordpress.com/2012/11/dietary001.jpg?w=316&resize=316%2C316&h=316#038;h=316&crop=1)